Sitting atop the piano at my aunt and uncle’s house, the smooth, clean lines of the carving attract my eye every time I visit. Worked all from one single piece of espresso-coloured wood, except for the staff she grasps tightly before her with both hands, the eight-inch sculpture is satin-finished and smooth. I can hold her in my hand, tracing the lines of the wood with my finger, her long skirts and cape swaying in an absent maritime breeze. Occasionally, the figurine will have moved since my last visit, decorating the mantle or the cabinet at the top of the stairs. Once, as I came in for a Sunday visit, I found her facing the front door from a hallway table. I would like to think she was waiting for me, welcoming me, but I suspect I was not the guest she hoped for.

Her name is Evangeline, and she has always been in the family, by way of carving, painting or bedtime story. Always, she is searching for her lost love. More than Cinderella or Sleeping Beauty, Evangeline’s was the story I remember most from my childhood, growing up in rural Nova Scotia. Growing up French in rural Nova Scotia, I should add. Like my childhood photos, accurate depictions paired with my hazy memories, blending real life into a child’s innocently inaccurate memory, I have made Evangeline my own. She is a part of who and what I am.

See, I am Acadian. Je suis Acadienne, just like Evangeline. A what, you ask? Good question. If I sound a bit sensitive, I am. Maybe it’s from a lifetime of correcting people who mispronounce my name. Sometimes, I just don’t even bother anymore. Perhaps I’m just overreacting. But then again, maybe I’m not. How can Canada officially have two languages if no one can even pronounce the most common French name in the world? There are celebrities with my last name. Here’s an example of a conversation I’ve had far too many times:

– “Luh-blonk (alternately pronounced ‘lee-blank’). Huh. You a frog, or somethin’?â€

– “LeBlanc. Like Matt LeBlanc, from Friends. And, while I’m not an amphibian, yes, I’m French — Acadian.†(or Acadienne, if I’m feeling particularly bilingual that day)

They look at me as though I’m stupid:

– “Oh. You mean Canadien, right?â€

Yes, that’s right: I’m twenty-nine, but unable to pronounce my own nationality.

– “No, Acadienne. ‘Ah-kay-dee-inn’. â€

– “Are you from Quebec?â€

– “No. I’m from Nova Scotia.â€

– “I didn’t know there were French people in Nova Scotia. I thought they were all, I don’t know, Scottish or something.â€

Sigh.

– “Nova Scotia was founded by the French. It used to be called Acadia, before they got the boot, and were deported to various unwelcoming places, including Louisiana, where they became known as Cajuns. You know: ‘Cajun.’ Like the food.â€

And this is where I inevitably lose my audience. They look away, shuffle their feet, and say they have to go and do something important they forgot about. No one likes being told they don’t know about something they should, especially if they don’t even care.

And these are Canadians I’m talking to. It seems that no one knows who or what Acadians are, or what they experienced almost 250 years ago. It’s no surprise, seeing as how it was all but erased from high school history books, and no one wants to take responsibility for what became of Acadia. But it’s a fascinating story, and a relevant one. People should know the origins of their country, and Acadians helped build the foundations of Canada as we know it.

Acadians came from France in 1605: the name Acadia, or L’Acadie, was given to the lands along the shores of the Bay of Fundy (today’s Nova Scotia and New Brunswick), as well as what we now call Prince Edward Island and parts of Newfoundland and Quebec.  The Acadians were mostly an agricultural people, trying to exist in an unfamiliar world, leaving Europe to get away from British and French warring, only to find the same thing an ocean away.

To make a long story short, the British ended up with ownership of Acadia, although Cape Breton remained French. The British gave the Acadians an ultimatum: swear loyalty to the British Crown, which would require renouncing their Catholic faith, or move to Cape Breton. The Acadians declined, twice.

So you know what the Brits decided? To hell with those darned non-partisan, pacifistic Acadians. They can just get lost. In fact, we’ll even help them with that, just to expedite matters. And so the Deportation of 1755—known by my people as the Expulsion of the Acadians, or Le Grand Derangement—saw some 6,000 Acadians shipped off to various places like Louisiana, Maryland and New York. Many didn’t survive, and those who did weren’t exactly welcomed with open arms and casseroles. Penniless and lost in a land of strangers, Acadians could hold only onto each other, their faith and their stories.

Years ago, my mother’s cousin sent me a stained glass Acadian flag. The attached card read, “Be proud of who you are: Acadian. Don’t ever forget where you are from.â€Â How could I forget? My family is about as Acadian as they come. Except for my grandfather’s side, who are Quebecois, my family tree is an Acadian one. That makes me three-quarters Acadian, one-quarter Quebecois, although technically Quebec was also part of Acadia, at least initially, in which case I’m the real deal, 100 percent, right down to my olive skin and dark hair.

“You might have to fudge it a little,†my mom says to me, as she hands me the handwritten genealogy, a cursive family tree, of my grandmother’s side of the family. My grandfather’s branches stretch back about 75 more years, give or take. On that side, we know our ancestors came to North America on the French equivalent of the Mayflower. That means I’m at least a seventh-generation Canadian, probably eighth or ninth. Except, I suppose it wouldn’t be Canadian yet. Acadian, then. But because Canada exists now, I’m confused. Does that make me an “Acanadian?â€

While we have little information about our ancestors prior to The Deportation, we can trace our lines back to Jean Jacques Deveau, who, rather than be deported, hid in the woods for some five years, probably with the help of the Mi’ qmak Indians. He ended up owning vast tracts of land from what is now Yarmouth to Meteghan. Earlier records may exist, since Deveau had been established in Acadia prior to Le Grand Derangement, but many families lost their records when they lost their homes and belongings. What wasn’t stolen was burned to the ground, including the churches, where records were best maintained. It takes time, patience and money to trace a bloodline, and in our case, the information may be lost forever.

Eventually, tales began to emerge about the displaced Acadians with a lost past: mythic accounts of loss and hardship—common themes shared by many. Evangeline is one of those stories.  She belongs to Acadia, a nation that had every material thing taken away from it, and was left with stories. These stories wove themselves into family histories, blending historical fact with sentimental fiction, until the one could no longer be told separately from the other. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow immortalized the Acadian history, as well as its heroine, in his 1947 poem, Evangeline. The epic tragedy was a huge hit, especially since it portrayed the British in a poor light (the depravity of the British being a popular theme for Americans at the time Longfellow wrote the poem), which cemented its place in historical American literature, though not so well, it seems, in its northern cousin’s.

My Evangeline is not Longfellow’s. In fact, I only just read his poem recently, and I have to say, it’s not nearly as romantic as the story I was told. Nor is it anywhere near as short. My Evangeline was given to me by my grandmother, or maybe my mother. Both actually, but I don’t remember when I heard the story the first time. The impression stuck, however; I can’t remember a time when I didn’t know the story, which goes like this:

Evangeline is a beautiful young woman living in Port Royal (now called Annapolis Royal—where I lived as a child) who falls in love with the handsome Gabriel, who adores her.

On the day they are to marry, the British show up with boats and ships. They set the villagers’ homes, churches and barns on fire, stealing all their belongings. Families are split up and sent away on different boats to different lands, never to see each other again. In the confusion, Evangeline and her love, Gabriel, are separated.

Evangeline spends her whole life wandering, trying to get home from Louisiana, where she landed after The Expulsion. She searches endlessly for her lost Gabriel, helping anyone who needs her along the way.

Finally, she arrives in Acadia (Nova Scotia by then), where she finds her beloved Gabriel on his deathbed. She is too late to save him, and her true love dies.

It’s not a happy story, I will admit. But it has haunted me more constantly than any other fairy tale I have ever known. I can see Evangeline, standing like my aunt’s carving, always just like that carving, on the ragged wild cliffs of Nova Scotia. The unforgiving Atlantic wind blows her long skirts behind her; she is a figure of beauty, grace and strength. She stands straight, while her long hair whips in the chilled breeze, holding her long staff like Moses’, as a symbol of righteousness, persistence, faith and true love.

In Evangeline, I can see myself, as I’d like to be. I identify in myself her longing for an earlier time that was happy and simple. I feel as though I could find this again, back at my childhood home, in a rural Nova Scotia that is cast in a glowing rosy tint of a perfect childhood. But then, my childhood wasn’t perfect. Not really. I realize now, from my adult perspective, that there was a tumultuous world of poverty and a heart- and family-shattering divorce beyond my naive childish eyes. Yet, I still see my life in sepia tones: faded colour snapshots of autumn leaves swirling down dirt roads, snow falling from a black sky, enveloping everything in a peaceful white silence. And it is perfect to me. It always will be. They say you don’t know what you have until you lose something dear. I don’t remember when I misplaced it, but what I want is lost to the past. Like Evangeline’s story, my history becomes fantasy.

Evangeline herself did exist, although not exactly as legend or Longfellow would have it. Originally Emmeline Labiche, an orphan, she was renamed Evangeline by her new guardians. Her love, not Gabriel, but Louis Arceneaux, was forced onto a different ship. Evangeline’s family left Maryland, where they were set down, to join other exiled Acadians in Louisiana. Here Evangeline found her Louis, but it is unclear whether she found him dying in a hospital or that he had agreed to marry another. Whatever the reason, the loss of her true love drove Evangeline over the brink of madness into insanity, and she eventually died from the wounds of her broken heart and mind.

Okay, so all this is 250-year old spilled milk, and certainly not the worst tale our stellar human history has to offer. But these stories need to be remembered. They are important, to Acadians, and to me.

Last year, on December 11, 2003, Queen Elizabeth II issued a royal proclamation, an official apology of sorts, to Acadian descendents everywhere. She decreed July 28 as a day of remembrance for The Deportation (July 28, 1754 was the day the deportation orders were signed). This is one of the first times the British government and monarchy have ever referred to the event. Thanks to an Acadian lawyer in Louisiana’s 10-year crusade, we finally got the apology we deserved—250 years later.

Better late than never, I suppose.

I have visited Nova Scotia, and fallen in love with it all over again, hearing the old stories, seeing the long-lost places and faces. Six years ago, my family brought me to Meteghan to visit the graves of my grandparents, on a sparse hill overlooking the bay. The waves on the beach of my childhood home in Annapolis Royal called to me. The leaves on the trees whispered, “welcome home,†in a raspy, wind-filled chatter. For a while, I could relive my childhood memories, immersing myself in my rose-tinted past. Could I have stayed? Of course. Would my perfect world fade, pushed aside by my adult one? I’m not sure. Uncertainty offers me solace: if I never test it, if I never know for sure, then I can hang on to my dream in the world of maybe and perhaps.

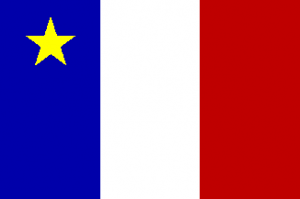

I have seen the Acadian flag all throughout the Maritimes—France’s flag, but for a small golden star at the top of the blue—and I see a people proud of their history. To Acadians, the colours of France have new meaning: blue for the sea, which took them away; white for peace and purity of heart; and red for courage and blood, the sufferings of our people. And the golden star? Like the star of Bethlehem, guiding Mary, the star is a guiding light to Acadians, bringing them home. It’s the star Evangeline followed home to Acadia, searching for her Gabriel.

As I look at my stained-glass Acadian flag in the window, and out beyond it to the stars in the night sky, I wonder if they filled Evangeline with courage, hope and direction. Will they do the same for me, if I follow them, too? And will I find what I’m looking for? Or, like Evangeline, will I discover I’m too late? That my home no longer exists, and that the perfect happiness I remember will fade away, like Gabriel dying in Evangeline’s arms, after a lifetime of searching?